Question the Question - Know the Right Question to Find the Real Answers

How many times have you gone out to a new restaurant and asked the waiter for advice?

“So, what’s your favorite dish?

“Should I get the Salmon or Sea Bass? Is the Filet tough?”

“If you had to pick one of these three which would you go with?”

We’ve all been there; and on the surface it seems like a great strategy – reach out to an “expert” that knows the product well, and they will provide at least some information to increase your odds of finding the winner. After all, many people are too stubborn, shy, lazy, or independent to get additional opinions. The active approach is far better than sitting back and taking a S.W.A.G. (scientific wild-ass guess) based off the witty wordsmiths who wrote the menu.

However, what seems like a simple interaction can often produce mediocre results. When the food comes out, and the dish doesn’t measure up to the plate across the table, the instinct is to blame the waiter as you perilously extend your fork over the flame for a bite of your partner’s lobster ravioli. Or, you could possibly discount the prior exchange, pretend the waiter isn’t expected to have all the answers, and you should just learn for the next meal.

But what if there was a better way. If your questions were altered just slightly is it possible that you would get a different answer?

Let’s table the idea and talk about a topic less recent, World War II.

—

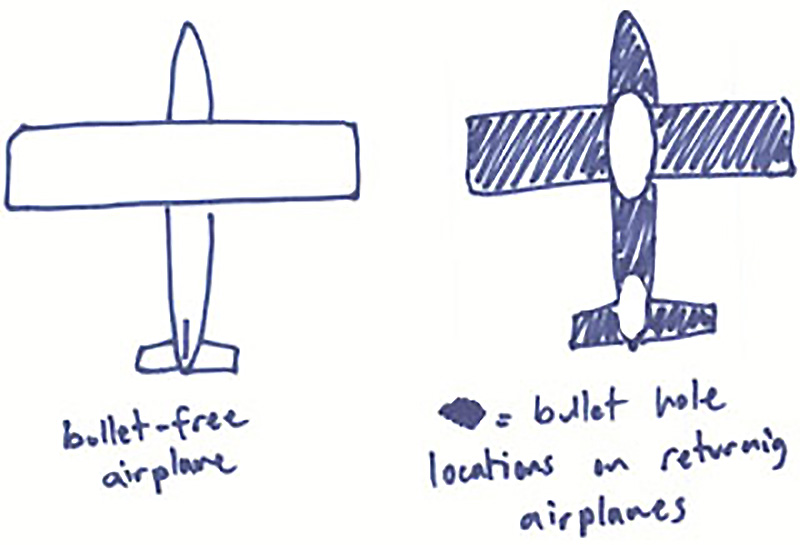

Back in the early 1940’s the allied forces wanted to increase the protection for their bombers; however, the planes could only add so much weight to still be able to fly long enough to complete their mission so they had to be selective. The military looked at their planes that came back from assignments and asked an obvious question, “Where are bullets most frequently striking the aircraft?” By looking at damage patterns the army assumed they could determine the danger zones and re-enforce the weak points. So, they added additional armor to the wings and tail gunner sections. Yet, there was no apparent reduction in plane fatalities.

Then a statistician named Abraham Wild helped change the War. He approached the problem with a simple, yet counterintuitive approach that would keep more planes coming home. Wild surmised that the bullet holes in surviving planes were not at the critical points. After all, these holes were on the planes which made it back to base. The holes really showed non-critical areas, as the planes still accomplished their missions with the damage and got home.

Instead he flipped the question around to focus on the planes that didn’t make it home – the ones nobody could examine. He theorized that since it was just as likely for a bullet to randomly hit the cockpit or tail-section, and the surviving planes were intact in these areas, it is probable that bullets in these regions caused the fatal strikes in planes that got destroyed. The “dead evidence”, named because it is ignored since it can’t be seen, is how Wild recommended the military shift their armor to the tail section.

The result was a dramatic reduction in fatal aircraft numbers. Wild’s genius was understanding Survivorship Bias: the logical error of examining and inquiring about apparent successes rather than unknown failures (or non-survivors depending on the situation) in order to draw conclusions. After all, if failures and the dead are not present, the focus naturally shifts to what’s visible. If you think about it, it is a human trend prevalent in every part of our lives:

In investing, people always want to know Warren Buffet’s secret to success.

Did he have some super skill that enabled him to deliver a 22% return over 36 years when average investor couldn’t squeak out a third of the annual return in the same period? Was it because his methods were so unique? Did nobody else follow his rules of selecting simple businesses, focusing on management teams or looking for a margin of safety?

The answer is to all these is clearly no, but we don’t want to hear from these “losers”, and they aren’t dying to talk to others about their losses; however, if more time was spend researching investors that failed to reach Buffet’s level we’d learn much more to help ourselves. We could gain insight into the additional mistakes others made; or the mindset that caused them to adjust their portfolios. Maybe we’d learn, as preposterous as it may seem, that luck just wasn’t on their side. As noted in the famous investing book, “Where Are the Customer Yachts?”, with millions of investors in the stock market, statistics will guarantee above average returns consistently by a couple hundred moneys picking stocks by throwing darts.

Another area with strong survivorship bias – sports.

The greatest athletes in the world year after year give such “original advice” on how they rose to the top. Magic worked harder than anybody else, staying hours before and after practice. Michael Jordan’s competitive fire could not be matched, whether it was basketball, checkers, or duck-duck-goose. Tiger Woods just “wanted it more”. – REALLY? It may be all true, but most amateur athletes probably know a half-dozen teammates that were so intense, competitive, or crazy they had to stop playing because their bodies couldn’t keep up with their minds.

If we studied minor league baseball players, or the guys that just failed to get drafted, it’s possible we would learn much more. These guys probably wanted it just as much, but were missing a few ingredients…or added too many. Few people remember the Len Biases or Ryan Leafs of the world, but asking them what not to do may be a better use of your time.

How about entrepreneurs?

Is the secret to success dropping out of school like Steve Jobs or Bill Gates? How many geniuses with great minds and business ideas have tried and failed using the same process? Frankly we have no idea because no books were written about these failures and they have no intention of speaking up; however, I’m guessing the odds are not good enough to be posted in Vegas.

—

This brings me back to dinner table and the decision on an entrée.

What if you flipped the question around and asked the waiter, “What are the least favorite entrees and why don’t they measure up?”

Sure, at first you may hear how every item on the menu is “unbelievable” and you can do no wrong, but if you push a little more, you may start to benefit.

“If you were forced to prioritize these items, which are at the bottom of the list.”

Eventually you get answers that are much more useful than asking about the best ones. They will usually open up and provide some insight that can assist in the other menu items that you should select. For example, maybe one dish isn’t great because ingredients are delivered the previous day – the same ingredients used in one of your top three choices.

The logic here can, and should, be used in every type of business setting. It is always more interesting to learn about projects that failed and why. Ask a salesman about the worst product features and you will get an idea of the quality in both the product and the man much faster than discussing the best-selling items. Is there dead evidence about a potential vendor; maybe instead of talking to their referrals who look at them as successful, talk to customers that didn’t form a partnership?

What do you think? Have you tried this before?

About the author: David Apollon is the managing director at 9Nation Inc., a consulting firm founded ten years ago to help Fortune 500 companies as well as growth-stage firms handle special IT and strategic projects including ERP, CRM and cloud-based implementations. David has led over 75 corporate programs, projects and PMO initiatives in the past 20 years.